Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

by Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell

Yale University Press

"Fashion, which its detractors have called slight, inconstant, fickle, and frivolous, is, however, fixed in its principles... We see how constant it is in seizing all remarkable events, adapting them, recording them in its annals, IMMORTALIZING them in memory."

~ Cabinet des modes, ou Les Modes nouvelles, 1786

"The dissemination of fashions follows the dissemination of ideas, and sometimes drives it."

~ Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell

Any visitor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City should stop by Gallery 599 on their tour of the museum. It's a small gallery, to get there you simply descend a small flight of stairs tucked away in the back corner of one of the large medieval galleries. Gallery 599 is located by the door to the Ratti Textile Center, which houses all of the textiles in The Met's collections. A rotating exhibition showcasing small samplings of The Met's textiles is featured in the display cases surrounding the door to the Ratti Textile Center. It's a quick pitstop on your tour of the museum and always well worth a visit as you get to see some rarely viewed textile treasures.

|

| Embroidery sample for a man's suit, 1800–1815. French. Silk embroidery on silk velvet; L. 13 1/4 x W. 11 1/8 in. (33.7 x 28.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The United Piece Dye Works, 1936 (36.90.15) |

One of the most famous and persistent images of the eighteenth century is a woman with an enormous tall wig decorated with ribbons, feathers, and all manner of figurines. Known as the pouf, this tall hairstyle is often cited as a visual representation of the excess of the 18th century. But these tall hairstyles were not just an example of extreme elite fashion. Often times these hairstyles were an expression of patriotism, politics, and the latest trends in culture. Today we may express our personalities and taste by wearing a T-shirt bearing the image of our favorite band, sports team, or the flag of our country. In the late 18th century, aristocratic women did the same thing using their hair.

|

| Anonymous, Coëffure à l’Indépendance ou le Triomphe de la liberté, c. 1778. In the collection of the Musée franco-américain du château de Blérancourt. |

Part 1: Snow White from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

As a fashion historian, I find that an interesting aspect of Disney is how the animated features serve as records of the visual culture of their day. The Disney Princesses, a successful sub-franchise launched by Disney in the late 1990s, are everywhere these days. They have not been without controversy, but they are certainly popular. They are also records of changing standards of beauty for women in the 20th century. This post series will discuss selected Disney Princesses, exploring how they embody the ideals of femininity of their time.

As a fashion historian, I find that an interesting aspect of Disney is how the animated features serve as records of the visual culture of their day. The Disney Princesses, a successful sub-franchise launched by Disney in the late 1990s, are everywhere these days. They have not been without controversy, but they are certainly popular. They are also records of changing standards of beauty for women in the 20th century. This post series will discuss selected Disney Princesses, exploring how they embody the ideals of femininity of their time.

Cinderella from Cinderella (1950)

La mode à la girafe translates to giraffe fashion, that is, fashion inspired by and celebrating giraffes. Or, in the case of late 1820s France, the fashion influence of one very famous giraffe.

|

| Nicolas Hüet, Study of the Giraffe Given to Charles X by the Viceroy of Egypt, 1827. In the collection of the Morgan Library and Museum. |

|

Left: Elizabeth Banks in Elie Saab Fall 2014 Couture

Top Right: Three robes a la francaise from the Kyoto Costume Institute

Bottom Right: Robe a la francaise, 1755-65, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fashion has always had a strong relationship with new technology. In the late eighteenth century, looms ran on punch cards to weave complex textile designs-- the very first computing technology. In the nineteenth century, the discovery of synthetic dyes allowed fabrics to take on bright, eye-popping colors. In the twentieth century, an enormous range of textiles made from synthetic materials, each with its own unique benefits, flushed the market. And in the twenty-first century, designers are using 3-D printers to create new and innovative designs.

Fashion has also always had strong ties with the media. New trends need to be disseminated around the world somehow, be it by illustrations, photographs, or film. These days we can log on to youtube and watch the latest runway shows instantly, but the relationship between film and fashion stretches much farther back in time.

Fashion has also always had strong ties with the media. New trends need to be disseminated around the world somehow, be it by illustrations, photographs, or film. These days we can log on to youtube and watch the latest runway shows instantly, but the relationship between film and fashion stretches much farther back in time.

In my work as curatorial assistant at the Chicago History Museum I was fortunate enough to study two beautiful court presentation gowns from the 1920s. I blogged about those dresses and the ritual of the court presentation on the Chicago History Museum Blog. But I also thought there was a bigger story to be told, and so I continue the story of these two gowns here on The Fashion Historian.

The first gown was worn by Mary Dudley Kenna when she was presented at the Court of St. James on June 10, 1926. It was designed by Jacques Doucet for the House of Doucet.

The second gown was worn by Mrs. Frederick L. Spencer,

née Helen Hurley, in the spring of 1928. It was designed by Edward Molyneux. To see images of both women in their court gowns, please refer to my post on the Chicago History Museum Blog.

Both of these gowns exhibit an extraordinary technical mastery, as can be seen by the detail images peppered throughout this post. But what I find most fascinating is the contrast these two gowns present-- one representing the romanticism of a bygone age, the other representing the sleek modernity of a new era.

Both gowns are well within the aesthetics of their respective designers. But just who were Jacques Doucet and Edward Molyneux?

Mary's gown was designed by

Jacques Doucet (1853-1929) for the House of Doucet. The House of Doucet was founded in 1817 by Antoine Doucet (1795-1866), Jacques' grandfather. Originally the house supplied lingerie, lace, and embroideries, a fitting beginning for a house that would come to represent a delicate, feminine aesthetic. In the early 1840s the house was established on the Rue de la Paix, one of the most important couture streets in Paris. Jacques himself was born there in 1853 and officially joined in the house in 1874. The House of Doucet was one of the largest couture houses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and some of the great couturiers of the twentieth century worked for Doucet including Paul Poiret (worked for Doucet from 1896-1900) and Madeleine Vionnet (worked for Doucet from 1907-1912). However, the firm never truly recovered from the ravages of World War I. It merged with a lesser couture house, Doueillet, in 1924, and closed altogether in 1932.

Captain Edward Molyneux (1891-1974) was born in London and served as a captain in the British army during World War I. He also worked for couturier Lucile in London before opening his own couture house in Paris in 1919. The House of Molyneux was an enormous success and branches were soon opened in Monte Carlo, Cannes, and London. Twentieth-century couturier Pierre Balmain apprenticed at the House of Molyneux, describing it in his 1964 memoirs, My Years and Seasons, as a "temple of subdued elegance... [where] the world's well-dressed women wore the inimitable two-pieces and tailored suits with pleated skirts, bearing the label of Molyneux."

The aesthetic of Jacques Doucet is colored by delicacy, romanticism, femininity, and a strong historical influence. Doucet himself was a great collector of 18th century art and his designs show the influence of the rococo aesthetic. Floral motifs and lace were particularly popular in his designs.

Mary's court presentation ensemble is certainly a fitting example of the Doucet aesthetic. The cut of the gown is in the fashionable 1920s style-- loose fitting and with a dropped waist. And yet the full, gathered skirt suggests the styles of a previous era. A sense of romance and whimsey, recalling the light aesthetic of the Edwardian period (1901-1910), is conveyed by the appliqued floral motif on both the gown and train. Soft velvets and satins are expertly stitched and gathered to create soft flowers which rest lightly in an embroidered basket. There is a playful whimsey as a few flowers and buds fall gracefully from the slightly tipped basket. Overall this dress conveys a sense of soft, delicate femininity. Compare it with the Doucet gowns below, from the early 1900s:

|

| Court presentation gown and train, Jacques Doucet, 1926. Gift of Miss Mary Dudley Kenna. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1965.380a-e. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Court presentation gown and train, Jacques Doucet, 1926. Gift of Miss Mary Dudley Kenna. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1965.380a-e. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Court presentation gown and train, Edward Molyneux, 1928. Gift of Mrs. Frederick L. Spencer. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1962.464a-d. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Detail of court presentation gown and train, Jacques Doucet, 1926. Gift of Miss Mary Dudley Kenna. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1965.380a-e. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Detail of court presentation gown and train, Edward Molyneux, 1928. Gift of Mrs. Frederick L. Spencer. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1962.464a-d. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Detail of court presentation gown and train, Jacques Doucet, 1926. Gift of Miss Mary Dudley Kenna. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1965.380a-e. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Detail of court presentation gown and train, Edward Molyneux, 1928. Gift of Mrs. Frederick L. Spencer. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1962.464a-d. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

|

| Detail of court presentation gown and train, Jacques Doucet, 1926. Gift of Miss Mary Dudley Kenna. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1965.380a-e. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

Mary's court presentation ensemble is certainly a fitting example of the Doucet aesthetic. The cut of the gown is in the fashionable 1920s style-- loose fitting and with a dropped waist. And yet the full, gathered skirt suggests the styles of a previous era. A sense of romance and whimsey, recalling the light aesthetic of the Edwardian period (1901-1910), is conveyed by the appliqued floral motif on both the gown and train. Soft velvets and satins are expertly stitched and gathered to create soft flowers which rest lightly in an embroidered basket. There is a playful whimsey as a few flowers and buds fall gracefully from the slightly tipped basket. Overall this dress conveys a sense of soft, delicate femininity. Compare it with the Doucet gowns below, from the early 1900s:

|

| Afternoon dress, Jacques Doucet, 1900-1903. In the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2009.300.579ab. |

|

| Ball gown, Jacques Doucet, c. 1902. In the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2009.300.3309ab. |

The same soft femininity of these two gowns from the Metropolitan Museum of Art is adapted to 1920s fashion in Mary's court presentation gown.

|

| Detail of court presentation gown and train, Edward Molyneux, 1928. Gift of Mrs. Frederick L. Spencer. In the collection of the Chicago History Museum. 1962.464a-d. Photo by Katy Werlin. |

In contrast to the historic romanticism of Doucet's aesthetic, the look of the House of Molyneux was all about modernity. Molyneux designs embodied the elegant and slim aesthetic of the 1920s and 1930s. His designs were restrained and avoided excess decoration, showing the influence of his military background and English heritage. Molyneux loved clean lines, and his designs were streamlined and fluid, taking inspiration from the new Art Deco style of architecture and design.

Helen's court presentation ensemble is the perfect example of this. The design is simple and clean, with lean, extenuated teardrop shapes made from concentric rows of pearls and crystals. All of these design aspects are hallmarks of the Art Deco movement. The dress itself is cut in a simple, narrow tube shape, embracing the most modern style of dress. Compare the design of Helen's dress with the Art Deco architecture below:

As you can see, Helen's dress fits right in with the sleek and modern style of Art Deco.

Helen's court presentation ensemble is the perfect example of this. The design is simple and clean, with lean, extenuated teardrop shapes made from concentric rows of pearls and crystals. All of these design aspects are hallmarks of the Art Deco movement. The dress itself is cut in a simple, narrow tube shape, embracing the most modern style of dress. Compare the design of Helen's dress with the Art Deco architecture below:

|

| The Chrysler Building in Manhattan, NY. Designed by William Van Alen and constructed from 1928-1930. |

|

| Ornamental ironwork designed by Edgar Brandt for the Cheney Silk building in Manhattan, NY (now the Madison Belmont Building). Built from 1924-1925. Photo by Daniel E. Russell. |

And so in these two dresses we see both the convergence of the past, the present, and the future. In Mary's dress Doucet adapts the delicate romanticism of the Edwardian aesthetic into the cleaner lines of the 1920s, while still maintaining a youthful, feminine charm. In Helen's dress Molyneux embraces the design of the future, adapting the ultra-modern Art Deco aesthetic into a trim gown that speaks of a new world.

The choice of these two designers most likely speaks to the personality of each woman. Perhaps Mary was more old fashioned and whimsical, while Helen embraced the new modern age. Each of these dresses gives us a glimpse of the women who wore them in an exciting era of change.

The choice of these two designers most likely speaks to the personality of each woman. Perhaps Mary was more old fashioned and whimsical, while Helen embraced the new modern age. Each of these dresses gives us a glimpse of the women who wore them in an exciting era of change.

Welcome to Carnivalesque #104! There's been all sorts of fascinating research being posted on the blogosphere, so let's take a look at what my fellow historians have been up to recently!

To start with some fashion history, the always wonderful Two Nerdy History Girls have been exploring just how those giant 1770s hairstyles were created. In Part 1 of this series they discuss a bit of the background of this hairstyle while busting some myths in the process. Part 2 takes a closer look at how Abby Cox and Sarah Woodyard, the mantua-maker's apprentices at the Margaret Hunter shop in Colonial Williamsburg, have been recreating these large styles themselves using period techniques.

Over on The Duchess of Devonshire's Gossip Guide to the Eighteenth Century, Heather Carroll tells us all about the fascinating Eglantine, Lady Wallace in her Tart of the Week feature. Eglantine, known as Betty, was a bit of a wild child and had many adventures during her life, including dressing as a man to watch a debate in the House of Commons and at one point being accused of espionage. I suspect Betty was a very fun person to hang out with.

Turning over to some books and manuscripts, guest blogger Julie Park discusses Interiority and Jane Porter's pocket diary at The Collation. Pocket diaries provide a world of information about 18th century life, and in this post Park looks at one from 1796 which belonged to Jane Porter, the first bestselling female author of historical fiction who wrote under her own name. In this fascinating post, Park explores how Jane Porter literally went outside the lines in her use of her diary, concluding that "Porter appropriates and repurposes the spaces of the diary to accommodate the vicissitudes of individual experience."

Earlier personal writing is explored in the post "My Well-Beloved Valentine", as Lucy Allen takes a look at the 15th century love letters of Margery Brews. Fun Fact: These letters contain the first recorded English use of the word Valentine as a synonym for lover. In this romantic post, Allen discusses how Margery Brews created a more personal language than that traditionally used between couples and started a tradition that continues to this day.

And in a final manuscript themed blog post, Jenny Weston at Medieval Fragments discusses Medieval Family Trees, exploring how medieval families documented their history and achievements in beautiful artistic detail.

Taking a break for some fun and games, Mike Rendell at The Georgian Gentleman takes a brief look at the history of the yo-yo and how, in the late 18th century, it had a brief period of popularity as one of the fashion accessories of the day.

And for some more active sports, Mike A. Zuber reports on early modern football at Praeludia Microcosmica. In this post Zuber links to some fascinating research about early modern football, noting that violence within the sport has a long history. Some games even led to death!

If you happen to be an ancient Babylonian suffering from epilepsy, Strahil V. Panayotov discusses how a doctor may have used fumigation to cure you at The Recipes Project. Panayotov writes, "Through fumigation the Babylonian medical practitioner could heal different illnesses: depression, epilepsy, troubles with the ears and the eyes, or even hemorrhoids." As the post goes on to reveal, the ingredients used to create this healing smoke could sometimes be a little odd. For epilepsy, the main ingrediant was parts of the head of a dead young male goat!

For those who enjoy tales of pirates, head over to English Legal History where Rebecca Simon discusses Pirate Executions in Early Modern London. Unlike many tales of the high seas, Simon's post explores the deadly fate of pirates who did not escape with their booty, and were instead taken to the Execution Dock and hung by the neck. In a particularly cruel twist, the nooses used for pirates were shorter than normal, meaning that a pirate's neck would not break as they dropped, causing them to die slowly of asphyxiation.

If all this fascinating reading has gotten you a bit hungry, why not head over to Early British and American Public Gardens and Grounds where Barbara Wells Sarudy looks at hunting, fowling, and shooting in 18th century America and Britain.

After all that meat you'll want a good drink, so head over to The Many-Headed Monster where Mark Hailwood gives his "Marooned on an Island" reading list all about the history of drinking. It is sure to fulfill all of your alcoholic history needs!

If all that food and drink has given you a bit of a stomach ache, then perhaps you should go to Les Leftovers where Jim Chevallier discusses shifts in fasting in medieval France. This detailed post considers what foods were and were not allowed on fasting days, when fasting days took place, and how all of this changed over time.

And that's all for this edition of Carnivalesque. I hope you have enjoyed exploring all of the amazing history that is available online as much as I have. Be sure to join us in September for Carnivalesque 105 at Meshalim/Amthal/Exiemplos: Notes from the Life of a Medievalist.

To start with some fashion history, the always wonderful Two Nerdy History Girls have been exploring just how those giant 1770s hairstyles were created. In Part 1 of this series they discuss a bit of the background of this hairstyle while busting some myths in the process. Part 2 takes a closer look at how Abby Cox and Sarah Woodyard, the mantua-maker's apprentices at the Margaret Hunter shop in Colonial Williamsburg, have been recreating these large styles themselves using period techniques.

Over on The Duchess of Devonshire's Gossip Guide to the Eighteenth Century, Heather Carroll tells us all about the fascinating Eglantine, Lady Wallace in her Tart of the Week feature. Eglantine, known as Betty, was a bit of a wild child and had many adventures during her life, including dressing as a man to watch a debate in the House of Commons and at one point being accused of espionage. I suspect Betty was a very fun person to hang out with.

Turning over to some books and manuscripts, guest blogger Julie Park discusses Interiority and Jane Porter's pocket diary at The Collation. Pocket diaries provide a world of information about 18th century life, and in this post Park looks at one from 1796 which belonged to Jane Porter, the first bestselling female author of historical fiction who wrote under her own name. In this fascinating post, Park explores how Jane Porter literally went outside the lines in her use of her diary, concluding that "Porter appropriates and repurposes the spaces of the diary to accommodate the vicissitudes of individual experience."

Earlier personal writing is explored in the post "My Well-Beloved Valentine", as Lucy Allen takes a look at the 15th century love letters of Margery Brews. Fun Fact: These letters contain the first recorded English use of the word Valentine as a synonym for lover. In this romantic post, Allen discusses how Margery Brews created a more personal language than that traditionally used between couples and started a tradition that continues to this day.

And in a final manuscript themed blog post, Jenny Weston at Medieval Fragments discusses Medieval Family Trees, exploring how medieval families documented their history and achievements in beautiful artistic detail.

Taking a break for some fun and games, Mike Rendell at The Georgian Gentleman takes a brief look at the history of the yo-yo and how, in the late 18th century, it had a brief period of popularity as one of the fashion accessories of the day.

And for some more active sports, Mike A. Zuber reports on early modern football at Praeludia Microcosmica. In this post Zuber links to some fascinating research about early modern football, noting that violence within the sport has a long history. Some games even led to death!

If you happen to be an ancient Babylonian suffering from epilepsy, Strahil V. Panayotov discusses how a doctor may have used fumigation to cure you at The Recipes Project. Panayotov writes, "Through fumigation the Babylonian medical practitioner could heal different illnesses: depression, epilepsy, troubles with the ears and the eyes, or even hemorrhoids." As the post goes on to reveal, the ingredients used to create this healing smoke could sometimes be a little odd. For epilepsy, the main ingrediant was parts of the head of a dead young male goat!

For those who enjoy tales of pirates, head over to English Legal History where Rebecca Simon discusses Pirate Executions in Early Modern London. Unlike many tales of the high seas, Simon's post explores the deadly fate of pirates who did not escape with their booty, and were instead taken to the Execution Dock and hung by the neck. In a particularly cruel twist, the nooses used for pirates were shorter than normal, meaning that a pirate's neck would not break as they dropped, causing them to die slowly of asphyxiation.

If all this fascinating reading has gotten you a bit hungry, why not head over to Early British and American Public Gardens and Grounds where Barbara Wells Sarudy looks at hunting, fowling, and shooting in 18th century America and Britain.

After all that meat you'll want a good drink, so head over to The Many-Headed Monster where Mark Hailwood gives his "Marooned on an Island" reading list all about the history of drinking. It is sure to fulfill all of your alcoholic history needs!

If all that food and drink has given you a bit of a stomach ache, then perhaps you should go to Les Leftovers where Jim Chevallier discusses shifts in fasting in medieval France. This detailed post considers what foods were and were not allowed on fasting days, when fasting days took place, and how all of this changed over time.

And that's all for this edition of Carnivalesque. I hope you have enjoyed exploring all of the amazing history that is available online as much as I have. Be sure to join us in September for Carnivalesque 105 at Meshalim/Amthal/Exiemplos: Notes from the Life of a Medievalist.

February is Black History Month! To celebrate here on The Fashion Historian, I asked my dear friend and colleague Elizabeth Way if she would pen a couple of guest posts about two incredible African American fashion designers and dressmakers and she kindly agreed. Enjoy!

Ann Lowe was a leading society dressmaker in New York City in the 1950s and 1960s. Her designs were so exclusive that she restricted her clients to those found on the Social Register; people with names like Roosevelt, DuPont, and Rockefeller. Her most famous design was for Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress, but she also made countless wedding and debutante gowns for American socialites. Anne Lowe made couture-quality gowns on par with the best French designers, true pieces of art that now reside in museums like the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. But before she came to New York, Lowe built her career as artistic and technically skilled fashion designer in Tampa, Florida.

Ann Lowe was born in 1898 in Clayton, Alabama. This was a rural town in the Jim Crow south, where most blacks struggled as sharecroppers, but Ann’s family was better off than even some white families because her grandmother, Georgia Cole, and her mother, Janey Lowe, were excellent dressmakers. Georgia was a former slave who had been bought and freed by her husband, a free black man named General Cole. When Ann was very young the family moved to Montgomery, and established a thriving business, fashioning gowns for the society ladies of the state capitol. Ann grew up picking up scraps from her grandmother and mother’s work and sewing them into beautiful replicas of the flowers she saw in the garden—these floral accents would become a signature of her designs. In 1914 Janey died suddenly, leaving her daughter to complete an important order for the governor’s wife. Sixteen-year-old Ann, not only finished the order, she took over her mother’s business. Her already advanced design and sewing skills made her a capable dressmaker, but when she married and gave birth to her son Arthur, her husband, Lee Cone, compelled her to give up her work and stay home with her family. Yet she never stopped designing—instead of sewing for socialites, she fashioned beautiful clothing for herself.

One day, Josephine Lee, a wealthy socialite from Florida, spotted a very fashionable young black woman from across an Alabama department store. Mrs. Lee was so impressed by Ann’s chic clothing she had to ask about them and when she found out that Ann made them herself, she hired the young woman on the spot as her live-in dressmaker. Mrs. Lee had four daughters who all needed fashionable clothes for the social season and Ann was to make them. Lee Cone was against the move, but Ann saw an opportunity to continue and expand the career she loved, and so she and Arthur boarded the train to Tampa.

In Florida, Ann’s career flourished. The Lee girls’ friends coveted their fashion-forward clothing and Ann was soon the most popular dressmaker in town. She was known for making original designs and working fast—sometimes a lady would drop by her shop in the morning with fabric for a dress that she could pick up and wear that night. The Lee family adored Ann and supported her growing talent—in 1917 they encouraged her decision to attend design school in New York City. Luckily for Tampa, its finest dressmaker returned after a year—Lowe was so skilled that she completed the course work of her design school in half the time, despite the fact that she was segregated to a separate classroom to work alone because of her race. Ann reopened her business and by the time she turned 21, she employed eighteen dressmakers in her shop.

Though Lowe made all types of garments, she was best known for exquisite ball gowns. Tampa hosted an annual social event called the Gasparilla festival, which was full of balls for the wealthiest residents. Young girls from the best families were elected to a Gasparilla court—the most popular was crowned the Gasparilla Queen—and they all wanted dresses by Ann. One socialite recalled, “If you didn’t have a Gasparilla gown by Annie, you might as well stay home.”

In interviews given late in her life, Ann Lowe always remembered her Tampa clients fondly and her time there as very happy. But she was destined for a bigger future. She made a permanent move to New York in 1928, again supported by the Lees who appreciated her talent and ambition. Yet, a local newspaper reported, “There is much ‘weeping and wailing and maybe gnashing of teeth’ to use the old expression, among Tampa society maids over the fact that Annie Cone [as she was known then] is going to New York City… feminine society is wondering just how it will be able to survive the future social seasons without her assistance.” Nearly forty years later, her Tampa clients still remembered their incredible designer. A Tampa Tribune article, written in 1965, included several interviews of Lowe’s Tampa clients and reported that, “everyone we spoke to who had an Ann Lowe gown remembers it distinctly and nostalgically.” The 1924 Gasparilla queen, Sarah Keller Hobbs, sentimentally recalled, “There was never anyone like Annie.”

Further Reading

Frye, Alexandria, “Fairy Princess Gowns Created By Tampa Designer for Queen In Gasparilla’s Golden Era”, Tampa Tribune, Feb. 7 1965, pp. 6-E.

Powell, Margaret, “The Life and Work of Ann Lowe: Rediscovering ‘Society’s Best-Kept Secret’”, (master’s thesis for the Smithsonian Associates and the Corcoran College of Art and Design, 2012).

Elizabeth Way, Curatorial Assistant at the Museum at FIT. Elizabeth wrote her master's thesis on the African American dressmakers Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe and continues to research the intersection of African American culture and fashion.

|

| Ann Lowe pictured in Ebony magazine in 1966. |

Ann Lowe was a leading society dressmaker in New York City in the 1950s and 1960s. Her designs were so exclusive that she restricted her clients to those found on the Social Register; people with names like Roosevelt, DuPont, and Rockefeller. Her most famous design was for Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress, but she also made countless wedding and debutante gowns for American socialites. Anne Lowe made couture-quality gowns on par with the best French designers, true pieces of art that now reside in museums like the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. But before she came to New York, Lowe built her career as artistic and technically skilled fashion designer in Tampa, Florida.

Ann Lowe was born in 1898 in Clayton, Alabama. This was a rural town in the Jim Crow south, where most blacks struggled as sharecroppers, but Ann’s family was better off than even some white families because her grandmother, Georgia Cole, and her mother, Janey Lowe, were excellent dressmakers. Georgia was a former slave who had been bought and freed by her husband, a free black man named General Cole. When Ann was very young the family moved to Montgomery, and established a thriving business, fashioning gowns for the society ladies of the state capitol. Ann grew up picking up scraps from her grandmother and mother’s work and sewing them into beautiful replicas of the flowers she saw in the garden—these floral accents would become a signature of her designs. In 1914 Janey died suddenly, leaving her daughter to complete an important order for the governor’s wife. Sixteen-year-old Ann, not only finished the order, she took over her mother’s business. Her already advanced design and sewing skills made her a capable dressmaker, but when she married and gave birth to her son Arthur, her husband, Lee Cone, compelled her to give up her work and stay home with her family. Yet she never stopped designing—instead of sewing for socialites, she fashioned beautiful clothing for herself.

|

| Gasparilla Court wearing gowns designed by Ann Lowe, 1927. Black Fashion Museum. |

One day, Josephine Lee, a wealthy socialite from Florida, spotted a very fashionable young black woman from across an Alabama department store. Mrs. Lee was so impressed by Ann’s chic clothing she had to ask about them and when she found out that Ann made them herself, she hired the young woman on the spot as her live-in dressmaker. Mrs. Lee had four daughters who all needed fashionable clothes for the social season and Ann was to make them. Lee Cone was against the move, but Ann saw an opportunity to continue and expand the career she loved, and so she and Arthur boarded the train to Tampa.

In Florida, Ann’s career flourished. The Lee girls’ friends coveted their fashion-forward clothing and Ann was soon the most popular dressmaker in town. She was known for making original designs and working fast—sometimes a lady would drop by her shop in the morning with fabric for a dress that she could pick up and wear that night. The Lee family adored Ann and supported her growing talent—in 1917 they encouraged her decision to attend design school in New York City. Luckily for Tampa, its finest dressmaker returned after a year—Lowe was so skilled that she completed the course work of her design school in half the time, despite the fact that she was segregated to a separate classroom to work alone because of her race. Ann reopened her business and by the time she turned 21, she employed eighteen dressmakers in her shop.

|

| Gasparilla Court wearing gowns designed by Ann Lowe, 1928. Black Fashion Museum. |

Though Lowe made all types of garments, she was best known for exquisite ball gowns. Tampa hosted an annual social event called the Gasparilla festival, which was full of balls for the wealthiest residents. Young girls from the best families were elected to a Gasparilla court—the most popular was crowned the Gasparilla Queen—and they all wanted dresses by Ann. One socialite recalled, “If you didn’t have a Gasparilla gown by Annie, you might as well stay home.”

In interviews given late in her life, Ann Lowe always remembered her Tampa clients fondly and her time there as very happy. But she was destined for a bigger future. She made a permanent move to New York in 1928, again supported by the Lees who appreciated her talent and ambition. Yet, a local newspaper reported, “There is much ‘weeping and wailing and maybe gnashing of teeth’ to use the old expression, among Tampa society maids over the fact that Annie Cone [as she was known then] is going to New York City… feminine society is wondering just how it will be able to survive the future social seasons without her assistance.” Nearly forty years later, her Tampa clients still remembered their incredible designer. A Tampa Tribune article, written in 1965, included several interviews of Lowe’s Tampa clients and reported that, “everyone we spoke to who had an Ann Lowe gown remembers it distinctly and nostalgically.” The 1924 Gasparilla queen, Sarah Keller Hobbs, sentimentally recalled, “There was never anyone like Annie.”

Further Reading

Frye, Alexandria, “Fairy Princess Gowns Created By Tampa Designer for Queen In Gasparilla’s Golden Era”, Tampa Tribune, Feb. 7 1965, pp. 6-E.

Powell, Margaret, “The Life and Work of Ann Lowe: Rediscovering ‘Society’s Best-Kept Secret’”, (master’s thesis for the Smithsonian Associates and the Corcoran College of Art and Design, 2012).

Elizabeth Way, Curatorial Assistant at the Museum at FIT. Elizabeth wrote her master's thesis on the African American dressmakers Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe and continues to research the intersection of African American culture and fashion.

February is Black History Month! To celebrate here on The Fashion Historian, I asked my dear friend and colleague Elizabeth Way if she would pen a couple of guest posts about two incredible African American fashion designers and dressmakers and she kindly agreed. Enjoy!

Elizabeth Keckly, the talented dressmaker and close friend to Mary Todd Lincoln, is resurfacing as an important historical figure. She appeared as a character in the film Lincoln (2012), played by Gloria Rubin, and her life has been the subject of several fictional and nonfictional books. This attention is well deserved because she was truly a remarkable woman—over the course of her life she bought her freedom from slavery, made a major impact on American fashion by dressing the most famous political wives of Civil War-era Washington DC, created a charity to aid newly freed slaves, and wrote her memoirs, leaving important documentation on both herself and the Lincoln family for future scholars. Though her experiences in Washington DC are fascinating history—she created fashions for every notable lady from Varina Davis, the first lady of the Confederacy, to all of Lincoln’s cabinet member wives—her story as a society dressmaker began on the western frontier.

Elizabeth was born a slave on the Burwell plantation in Dinwiddie County, Virginia in 1818. Her mother was Agnes, also a slave and the head seamstress and dressmaker to the Burwell family. Her father was Armistead Burwell, Agnes’ owner and the master of the plantation. Agnes taught her daughter not only to sew and make dresses, but also to read and write, empowering Elizabeth with valuable skills for her future. Elizabeth moved several times in her enslaved life because her father lent her out as help to her half-siblings. After living in Hillsborough, North Carolina, where she was raped by a white man and gave birth to her son George, and Petersburg, Virginia, she moved to St. Louis, Missouri in 1847 as a slave to her half-sister, Anne Burwell Garland and her husband Hugh Garland.

Hugh Garland was a lawyer, and the family was socially well connected, but he suffered from very poor finances. He sent Elizabeth out as a dressmaker to support the family and for two years and five months she worked as the main breadwinner supporting seventeen people! Elizabeth had gained her first experience sewing gowns for her Burwell half-sisters and was quite accomplished by the time she moved to St. Louis. However, the ladies in this city truly prepared her for the success she found in Washington. They demanded the latest French fashions, which they read about in magazines or picked up from visits and friends in New Orleans. These lady patrons, who refused to give up looking fashionable just because they lived in far-flung St. Louis, sharpened Elizabeth’s dressmaking skills and refined sense of style.

Elizabeth was intelligent, talented and an excellent businesswoman; in her own words, “in a short time I had acquired something of a reputation as a seamstress and dress-maker. The best ladies in St. Louis were my patrons, and when my reputation was once established I never lacked for orders.” Therefore, it is no surprise that this black female slave, who could support a family better than a formally-educated white man, would want to move beyond the limitations of slavery. Elizabeth repeatedly asked Hugh Garland to set a price for her and George’s freedom, which he finally did: $1200. This was an enormous amount of money, especially considering that most of her wages went to the Garlands. But the always-enterprising Elizabeth had a plan. She would travel to New York City and seek financial aid from one of the abolitionist organizations that helped slaves purchase their freedom. By this time Hugh Garland had died and Anne Garland agreed to let Elizabeth travel north, but only after acquiring the signatures of six white men who would pay her value to Anne if she never returned. Elizabeth had no problem obtaining these pledges because her clients and their husbands knew her as honest and trustworthy. The sixth man, however, spoiled her plans. This Mr. Farrow would willingly sign for her, but was convinced that she would never come back to St. Louis telling her, “you mean to come back, that is, you mean so now, but you never will. When you reach New York the abolitionists will tell you what savages we are, and they will prevail on you to stay there; and we shall never see you again.” Elizabeth was morally shocked that Mr. Farrow thought she was lying and called off her trip, explaining, “I was beginning to feel sick at heart, for I could not accept the signature of this man when he had no faith in my pledges. No; slavery, eternal slavery rather than be regarded with distrust by those whose respect I esteemed.”

In her darkest hour, Elizabeth was saved by the reputation she had earned and the loyalty she inspired, not simply as an excellent dressmaker, but as an admirable and respected person. A client, Mrs. Le Bourgois, came to visit and told Elizabeth that her patrons did not want her to go to New York and beg for money for her freedom. Instead Mrs. Le Bourgois raised the $1200 among Elizabeth’s clients, gifting her with the money. In 1855 Elizabeth bought her and George’s freedom and she started her own business as a free dressmaker in St. Louis. She repaid every penny given to her by her patrons and in 1860 Elizabeth Keckly arrived in Washington DC, beginning her illustrious career as the leading dressmaker in the nation’s capitol.

Further Reading

Keckly, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave and Fours Years in the White House. New York: G.W. Carlton and Co. Publishers, 1868.

Elizabeth Way, Curatorial Assistant at the Museum at FIT. Elizabeth wrote her master's thesis on the African American dressmakers Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe and continues to research the intersection of African American culture and fashion.

|

| Elizabeth Keckly in the 1860s. Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, Indiana. |

Elizabeth Keckly, the talented dressmaker and close friend to Mary Todd Lincoln, is resurfacing as an important historical figure. She appeared as a character in the film Lincoln (2012), played by Gloria Rubin, and her life has been the subject of several fictional and nonfictional books. This attention is well deserved because she was truly a remarkable woman—over the course of her life she bought her freedom from slavery, made a major impact on American fashion by dressing the most famous political wives of Civil War-era Washington DC, created a charity to aid newly freed slaves, and wrote her memoirs, leaving important documentation on both herself and the Lincoln family for future scholars. Though her experiences in Washington DC are fascinating history—she created fashions for every notable lady from Varina Davis, the first lady of the Confederacy, to all of Lincoln’s cabinet member wives—her story as a society dressmaker began on the western frontier.

Elizabeth was born a slave on the Burwell plantation in Dinwiddie County, Virginia in 1818. Her mother was Agnes, also a slave and the head seamstress and dressmaker to the Burwell family. Her father was Armistead Burwell, Agnes’ owner and the master of the plantation. Agnes taught her daughter not only to sew and make dresses, but also to read and write, empowering Elizabeth with valuable skills for her future. Elizabeth moved several times in her enslaved life because her father lent her out as help to her half-siblings. After living in Hillsborough, North Carolina, where she was raped by a white man and gave birth to her son George, and Petersburg, Virginia, she moved to St. Louis, Missouri in 1847 as a slave to her half-sister, Anne Burwell Garland and her husband Hugh Garland.

|

| Keckly designed this silk velvet and satin gown for Mary Lincoln in 1864. National Museum of American History, Political Life Division. |

Hugh Garland was a lawyer, and the family was socially well connected, but he suffered from very poor finances. He sent Elizabeth out as a dressmaker to support the family and for two years and five months she worked as the main breadwinner supporting seventeen people! Elizabeth had gained her first experience sewing gowns for her Burwell half-sisters and was quite accomplished by the time she moved to St. Louis. However, the ladies in this city truly prepared her for the success she found in Washington. They demanded the latest French fashions, which they read about in magazines or picked up from visits and friends in New Orleans. These lady patrons, who refused to give up looking fashionable just because they lived in far-flung St. Louis, sharpened Elizabeth’s dressmaking skills and refined sense of style.

Elizabeth was intelligent, talented and an excellent businesswoman; in her own words, “in a short time I had acquired something of a reputation as a seamstress and dress-maker. The best ladies in St. Louis were my patrons, and when my reputation was once established I never lacked for orders.” Therefore, it is no surprise that this black female slave, who could support a family better than a formally-educated white man, would want to move beyond the limitations of slavery. Elizabeth repeatedly asked Hugh Garland to set a price for her and George’s freedom, which he finally did: $1200. This was an enormous amount of money, especially considering that most of her wages went to the Garlands. But the always-enterprising Elizabeth had a plan. She would travel to New York City and seek financial aid from one of the abolitionist organizations that helped slaves purchase their freedom. By this time Hugh Garland had died and Anne Garland agreed to let Elizabeth travel north, but only after acquiring the signatures of six white men who would pay her value to Anne if she never returned. Elizabeth had no problem obtaining these pledges because her clients and their husbands knew her as honest and trustworthy. The sixth man, however, spoiled her plans. This Mr. Farrow would willingly sign for her, but was convinced that she would never come back to St. Louis telling her, “you mean to come back, that is, you mean so now, but you never will. When you reach New York the abolitionists will tell you what savages we are, and they will prevail on you to stay there; and we shall never see you again.” Elizabeth was morally shocked that Mr. Farrow thought she was lying and called off her trip, explaining, “I was beginning to feel sick at heart, for I could not accept the signature of this man when he had no faith in my pledges. No; slavery, eternal slavery rather than be regarded with distrust by those whose respect I esteemed.”

Keckly's Deed of Emancipation and Freedom Bond, 1855. Missouri Historical Society.

In her darkest hour, Elizabeth was saved by the reputation she had earned and the loyalty she inspired, not simply as an excellent dressmaker, but as an admirable and respected person. A client, Mrs. Le Bourgois, came to visit and told Elizabeth that her patrons did not want her to go to New York and beg for money for her freedom. Instead Mrs. Le Bourgois raised the $1200 among Elizabeth’s clients, gifting her with the money. In 1855 Elizabeth bought her and George’s freedom and she started her own business as a free dressmaker in St. Louis. She repaid every penny given to her by her patrons and in 1860 Elizabeth Keckly arrived in Washington DC, beginning her illustrious career as the leading dressmaker in the nation’s capitol.

Further Reading

Keckly, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave and Fours Years in the White House. New York: G.W. Carlton and Co. Publishers, 1868.

Elizabeth Way, Curatorial Assistant at the Museum at FIT. Elizabeth wrote her master's thesis on the African American dressmakers Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe and continues to research the intersection of African American culture and fashion.

Right: Image from 13th century Bestiary. British Library, Royal ms 12 F XIII f9r.

Sometimes fashion is for the dogs. Just a silly little historic influence post for the weekend! Many thanks to @tudorcook for the manuscript image.

"The Robe she ware was lawne (white as the Swanne)

Which silver Oes and Spangles over-ran

That in her motion such reflexion gave,

As fill'd with silver stares, the heav'nly wane."

- John Davies of Hereford, An Extasie, 1603

What better way to return from a long hiatus than with a flurry of sparkles? Today's post is all about sequins, spangles, and oes!

|

| French court suit jacket, 1750-75. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

For centuries, the fashionable have decorated their clothing and accessories with small, reflective metal discs. Today we know these as sequins, but in previous centuries they were known as spangles. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recorded use of sequin as a name for these sparkly discs was in 1882. A few centuries earlier, a sequin was the name of an Italian gold coin. Perhaps this reference to a small disc of precious metal inspired the later use of the word.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, sequins were known as spangles or spangs. Spangles were made of precious and semi-precious metals such as gold, silver, and copper, and came in a variety of shapes and sizes. The most common was the flat, circular disc we are familiar with today. But by the end of the 18th century, spangles could be cut into multiple shapes like clovers and hearts, and could be tinted colors like pink and blue. In many descriptions, such as the poem at the beginning of this post, spangles are paired with oes. Oes were another form of decorative metal detail, very similar to spangles. According to scholar M. Channing Linthicum, "oes were metal eyelets tacked or clinched to the material in such designs as 'squares,' 'Esses,' 'wheate eares,' etc., or powdered over the whole surface."

|

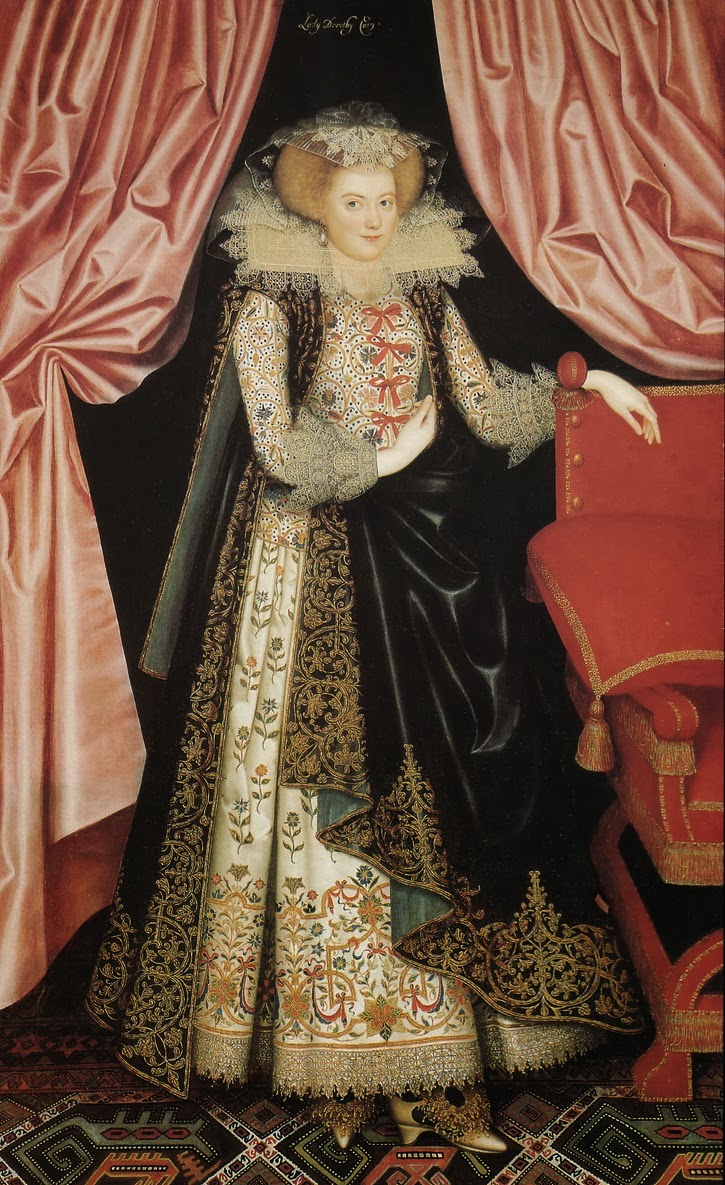

| Lady Dorothy Cary by William Larkin, c. 1614. English Heritage. The little spots on her embroidered jacket are spangles. |

According to records of English parliamentary proceedings, in 1575 "a Patent was first granted to Robert Sharp to make Spangles and Oes of Gold." This suggests that Robert Sharp was perhaps one of the first English manufacturers of spangles and oes, or perhaps an innovator in their production. There were two methods for creating spangles. In the first method, a thin coil of wire was wrapped around a narrow dowel. The resulting spring was then cut and the coils hammered flat to create round discs with a small hole in the middle. The second method was used to create spangles with more elaborate shapes. In this method, a thin sheet of metal was laid out and the spangles were punched out using shaped tools, like when you make cookies with cookie cutters.

Spangles and oes were used to decorate the clothes and accessories of men and women. In the candle light, they would shimmer and lend a magical quality to the wearer. In an essay by Francis Bacon, titled Of Masques and Triumphs, the glittering effect of spangles and oes is described. He writes, "The colors that show best by candle-light are white... and oes, or spangs, as they are of no great cost, so they are of the most glory."

|

| Women's Jacket made in Great Britain, 1600-1625. The Victoria and Albert Museum. |

Over the years, spangles and oes have decorated a variety of garments and accessories. One of the most notable uses was in the first decades of the 17th century when they covered women's embroidered jackets, as in the above image. From 2007 to 2009, workers at Plimoth Plantation meticulously reproduced one of these embroidered jackets. To read more about this incredible undertaking, including their manufacturing of spangles, I highly recommend their blog.

|

| Detail of a French court suit embroidered with blue tinted spangles, 1750-75. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, spangles could often be found on decorative embroidery. The above image is a detail of the court suit pictured earlier in this post. Here you can see a variety of spangles, from plain gold circles to blue tinted circles and pointed ovals. As for the tightly coiled wires which surround many of the spangles, could they be oes?